10 May, 2024.

This morning Tohunga Whakairo Rākau (Master of wood carving) Clive Fugill has been made a companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to Māori Art at Government House.

Clive (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngai Te Rangi, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Rangiwewehi) has been with the New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute (NZMACI) since its first intake in 1967 and still takes lectures for tauira (students) at 75 years-old today. He receives this honour, 64 years after his teacher, Tohunga Whakairo Rākau Hōne Te Kāuru Taiapa received an MBE for wood carving himself in 1960.

We sat down to ask Koro Clive, or ‘chiefy’ about his life.

Koro Clive, what it means to you to receive this honour today?

Just three words really – honoured, humbled and thankful.

And why those things?

Well, honored because, you see people getting these Royal Honours and you never think you’re gonna get one yourself.

Then of course humble at the same time because, it’s not just you getting it, it’s all the people and organisations who have supported you over the years. This includes Te Puia and the New Zealand Māori Arts & Crafts Institute; my good lady at home Noa, she’s helped me a hell of a lot you know – she looks after me; and my parents back in the day.

The other thing is, because of all of that, you’re thankful. After all the years of hard work that you’ve put in and the struggles along the way – it’s special to be recognised for the work that you’ve done.

What does this mean for Aotearoa to see Māori Art, Whakairo Rākau, recognised at a Royal New Zealand Honour level?

I hope this is a motivation for these young fellas, the tauira, to keep learning and doing what they’re doing. It’s interesting that this Royal New Zealand Honour has come around now – it’s 60 years of the New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute Act. The Act’s purpose is to preserve, promote and perpetuate Māori arts, crafts and culture – it is the very thing that pushes me to do what I do. To keep the Act alive and active!

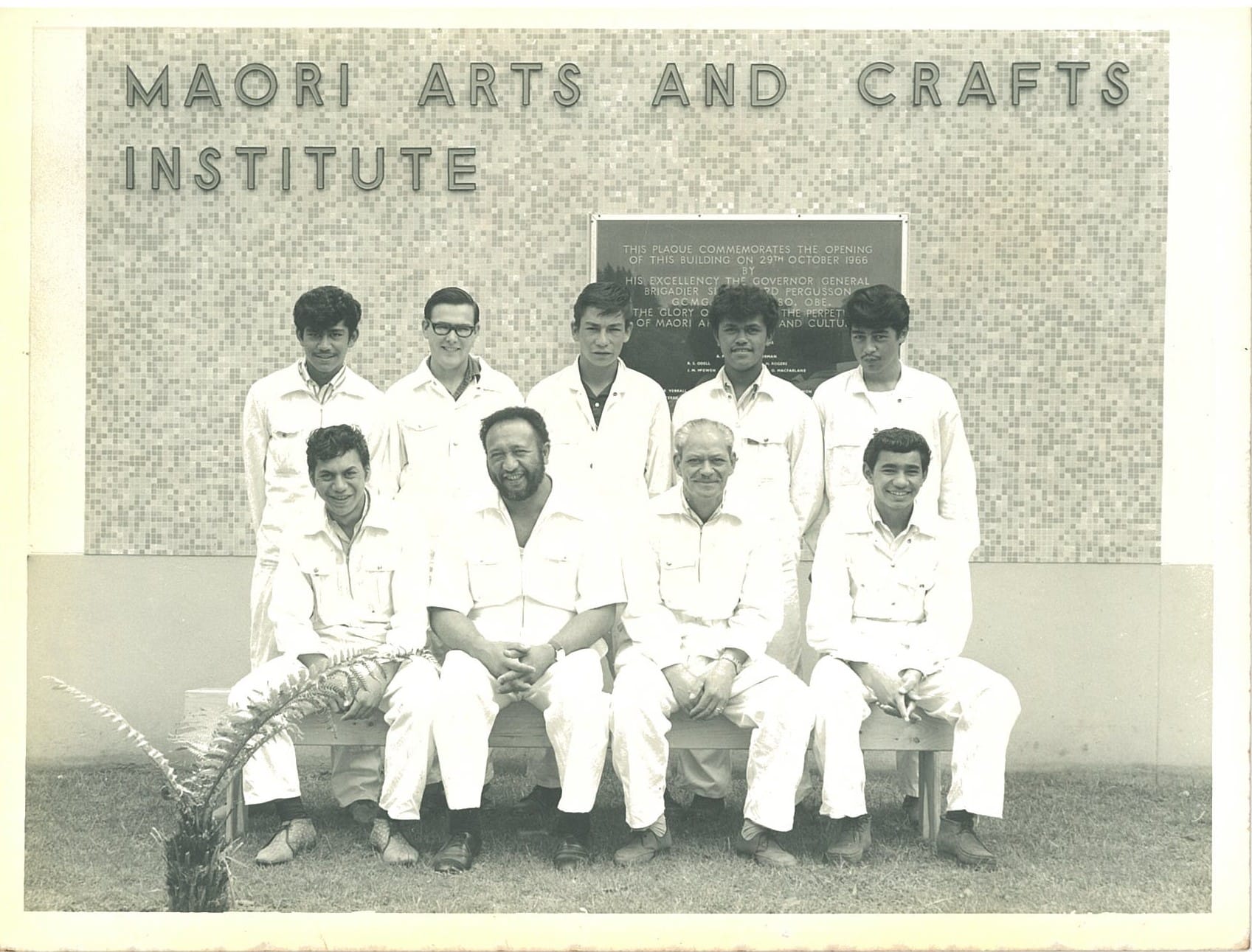

The first intake of tauira (students) in 1967.

You mentioned there’s been people and places that were important on your journey, including your parents. So how did your parents help you on your journey?

My family were all bushmen. They worked in the forest as contractors in blocks of bush over the back road to Tauranga, through Mangorewa Gorge and also out the back of Ngongotahā. My father worked in the old National Timber Company in the ’20s and ’30s. Dad would bring firewood home and it was all native, so I learnt native timber and what features types of wood had.

I learnt a lot from my father because he virtually lived in the bush. He knew all the trees. He knew Māori rongoā. I got a lot of his practical knowledge, but I spent time in the woodshed with a pocketknife. That’s how my interest started.

In 1962 when I was 12 my parents gave me a set of six Miller Falls, America carving tools and some books on Māori carving. Then my mother gave me a set of flat chisels. I’ve still got those. I took to it like a duck to water – it was quite common to see me come home with an old tōtara fence post over my shoulder, to be cut up and carved. Then I started doing souvenirs for Paradise Valley. I was still at school and effectively I had a business running with my hobby – it just went from there.

My neighbour, Dave Winterburn (Ngāti Raukawa) carved at the Buried Village, he was talking to dad over the fence one day. He heard this tap, tap, bang, bang in the shed and dad told him I was doing Māori carving. He hopped over the fence and had a look. “It’s not bad. I think you want a bit of help mate,” he said. “Meet me down at my kitchen Saturday morning, seven o’clock and I’ll take you out to the Buried Village.” So he used to take me out there and I learnt a lot about the business side of things. I started working there.

When I got to Rotorua Boys High School, I saw all the carving around the stage that John Taiapa and Jim Ruru had done. I used to stare at that and say – that’s what I want to do. I want to carve like that. I never realised that I was going to meet the man and then be under him for 13.5 years.

How did it come about that you applied to get into NZMACI?

My neighbour Dave said to my father one day – “why don’t you get him to apply for the carving school?” That was 1966. And, dad thought that was a good idea. Dave said I’d have some trouble getting in with a pākehā appearance and he was right.

However, dad had this photo here which he showed NZMACI (Clive shows me a beautiful old photo that sits on a shelf next to his desk).

It shows five generations of Māori whakapapa – my great great great grandmother who died aged 108, my great great grandmother, my great grandmother, my grandmother and my dad’s older sister. The oldest child in each generation and they were all girls.

Since then, I’ve researched my whakapapa and created a book for our family which I’m still working on – I have 80 tables in there showing our whakapapa.

So after dad showed the photo, they sent someone round to interview me from Māori Affairs. He came in and looked at all my work and said – “tell me what these mean?” I told him everything. He responded, “you know more about it than I do, boy.” And wrote down highly recommended.

Then I got two letters on Christmas. One from the education department with my school certificate results – I’d missed out by 20 marks – I should have put a recount cause I worked like hell to get that. The second letter said I’d been accepted into the first NZMACI carving school for the first intake. So, the path had already been set.

If you can reflect on 60 years with NZMACI, what are some things that really stand out for you when you think of the legacy of this place?

Well, I can only go from my own experience. My first encounter with NZMACI goes back to June of 1966. I was 17 and still in high school, and I came up here to get my application form for the school. At that time, there was nothing on the site. There was only the model pā and the old Ngongotahā Post Office.

The building was completed in October 1966 and opened by Sir Bernard Ferguson, who was the Governor General at the time.

Hone Taiapa was the master carver at the time, and the other tutor was Tuti Tu Kaokao.

There were seven of us that started: James Rickard, Wallace Hetaraka, Tutu Honotapu, Kapua Riini, Hoani Korako Arahanga, Jimmy Fergus and me.

We all came from various iwi around the country because it was pan-tribal. The idea was to (under the Act), teach young men the art and they would take it back to their own iwi and pass the knowledge on. That’s always been the case.

First intake of tauira (students) first day

What was that first year like?

Well, in the first year we started off doing teko teko first. The Post and Telegraph Department were replacing all their old tōtara telegraph poles: we ended up with them, all solid tōtara. From a block we’d cut a piece so long, then we had to clean all the rubbish and stuff off the outside to get to the good wood inside. That’s what we made our first tekoteko from.

We did two each of those and once we’d completed the moulding stage without any surface patterning on it, Hone got us to do some surface practice boards. Once we’d completed the patterns, we’d put the pattern onto the tekoteko.

We’d only been here about three months or so and Hone got us to finish off what work was left on St Faiths Church.

And then straight after that, we had to complete work on a meeting house: Hangarau at Tauranga, one of my own marae’s from home.

So, the first six months was pretty busy for us; full on. After that, we started to do some smaller work, smaller pieces.

In our second year, we worked on carvings for:

- the THC International Hotel at Whaka.

- Te Whatumairangi meeting house at Parawai Marae, Ngongotahā.

- a few other bits and pieces.

In our third year we worked on the DB Hotel (now called Copthorne Hotel Rotorua). That included carving and tukutuku. That was our first experience of doing tukutuku (also called turapa). We also had to learn how to put the frames together.

Luckily for me, I kept records of everything. I was the only one that did. I have records of those frames being done, plus all of the carving that we did in the carving school, the big carving, everything. I recorded it on paper when I was a student; that helped me with my drawing skills.

I ended up with a really good knowledge of patterns at the end of my studies, and through the carvings for that hotel.

And then I think we worked on the RSA building. That included tukutuku again, and carving.

By the time we finished our studies, I think the only thing we didn’t do was kōwhaiwhai painting. We all knew the patterns because you draw them in wood as well as carving them in wood.

We were doing smaller work as well like patu, waka huia and sewing boxes.

It was a pretty full on three years. By the end of it, we were well grounded. It was awesome.

What was Hone Taiapa like as a tutor?

One of the best teachers.

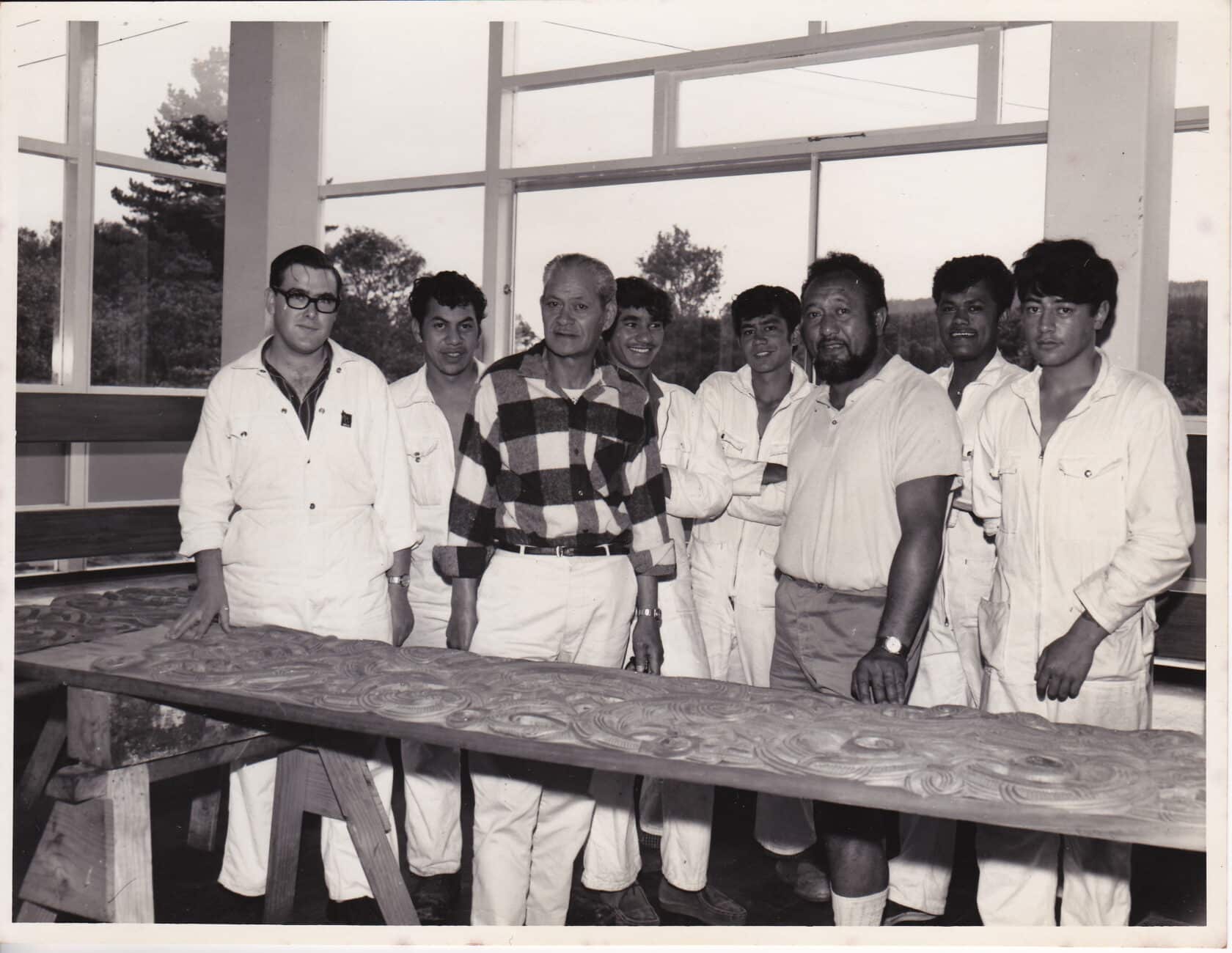

Hone Taiapa with the first intake

And why was that? Could you tell me a bit about his style?

Hone would come over and have a look when you made a mistake, see what the boo-boo was and show you how to fix it.

He always had a saying: “the man that makes all the mistakes will learn everything. The man that makes no mistakes will learn nothing.”

And he had a good way of teaching too. He said, “when you’re looking at students, the first week or so will tell you who’s pretty bright, who’s not so bright and who’s struggling.”

So, a good tutor will look at the ones that are quite bright, show them what to do and they’ll do it. The ones that are not so bright may have a little bit of trouble, so you help them a little bit. Your focus is primarily on those who are having difficulty. You help them to bring them up to the level of the bright students. That’s the mark of a good teacher!

He was a very good teacher. There wasn’t any boo-boo that he couldn’t fix in other words.

He had another saying too, “there’s always a way”.

Those are pretty important sayings. I can see how they stuck with you.

He was an amazing person Hone, because to me he was the only one that could build a meeting house from the concrete foundations to the last stick of carving, tukutuku, kowhaiwhai, everything.

He could do it all himself. He had the knowledge to do it because he wasn’t just a master carver, he was a master builder as well and he had all the tickets to prove it. That’s why I stuck to him like glue.

You could recognise how special he was.

I tried to get as much information as I could from him. I thought it was only for my own curiosity. But then as time went by, I realised, it’s not just for my sake but for these younger ones coming along.

The knowledge is to pass on, to share. That’s what we’re supposed to do. What I’ve learnt from him is starting to come into its own now. But those first three years were full on, really full on.

Do you find the teaching style you’ve developed over the years is very much influenced by that experience?

Oh yeah, very much, yeah.

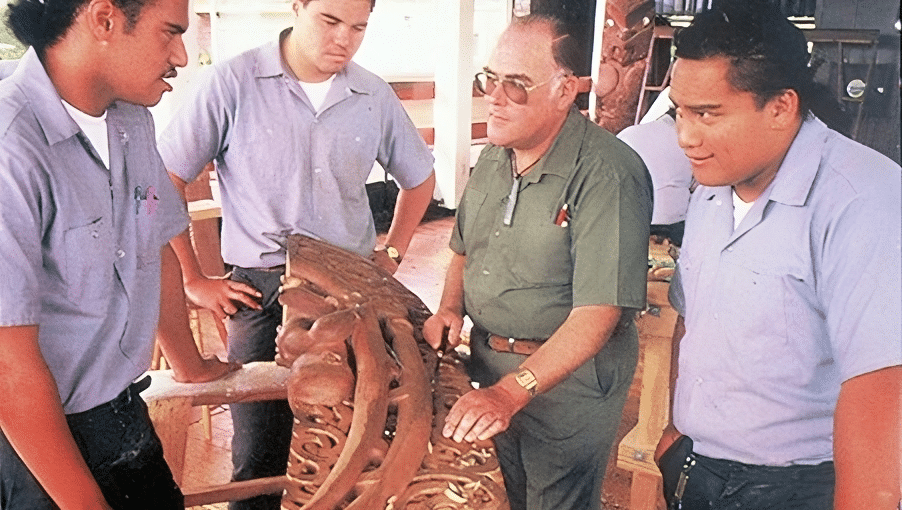

Clive working with tauira

What would you say your teaching style is?

Well, I try to emulate what Hone had done. I remember my first experience of teaching. It was 1976 and we’d just come back from the Christmas holiday break, We had just started work and he called me into the office, and he said to me “there’s four boys out there, go teach them. You know what to do”. That’s all he said.

I had to go down and get all their tools out for them, show them how to sharpen them if they needed sharpening, go and get their wood, and start them off on their first tekoteko.

I worked out in my own mind about how to teach these guys how to make tekoteko in a quick and easy way without too much hassle. I had to work out a system to do that and it ended up working out really well. After a week we had four tekoteko all moulded. They were sitting on a bench, and he came out of his office, had a look, a big smile appeared on his face, then he walked back into his office and continued reading his paper. I must have done something right.

That smile told you everything!

So, I got these guys through their first lot of training and then the next intake that came in, I ended up doing the same. I was putting them through their first stages of training. That was my introduction to teaching.

You said that when it came to teaching the students how to make tekoteko, you had to work out your own system to do that. What system did you come up with?

We weren’t allowed to use the bandsaw to outline anything, you had to do everything by hand. Hone’s reasoning for that was that when the students return to their kāinga (home), not everyone would have bandsaws or all that equipment. They’d probably have handsaws and all the basic stuff. So, the thing was to teach them how to use basic tools to do their work. Bandsaws would come later, which it did.

So, we had to get them to cut pieces out with an ordinary handsaw, take all the waste out to profile it, from the profiling then you start to do the rolling over, then pouring holes through all of that until you get to the last stages of the moulding process where you’re rolling everything over. Then from there you’re putting the details in like hands, toes, noses and all the rest of it, eyes and things. And then from there, you start the process of the practice board and all the designs that they’ve got to learn, so once they’ve perfected the practice board the pattern goes on to the tekoteko. Exactly how he taught us. Same methodology but you work out your own system to do it.

So, 60 years on, the way Hone Taiapa taught how to do that first piece of work when you came in as a student, the tekoteko, is that how it is still taught today?

It’s back to doing that.

The programme today is:

- Year One – they learn the tekoteko.

- Year Two – they learn all the different tribal styles.

- Year Three – they do the smaller items like waka huia, all the different weapons, taonga puoro (musical instruments), feather boxes.

And of course, there might be a big project that comes up in the middle of it so then they get the bigger work. The idea is to give them a good grounding in everything.

And when we reflect on 60 years, if you were to say to someone who had no background or history really on NZMACI what the significance of this place is and what the legacy of it is, what would you say?

Well firstly it’s not the first time that there’s been a revival in Māori arts and crafts. The first one goes back to 1926. Sir Apirana Ngata lobbied for an Act of Parliament, so a school was set up at that time. Hone Taiapa was a student in that school and the idea was to perpetuate, maintain and carry on Māori arts and crafts because they were virtually dying out. He wanted to revive these things. That school petered out around 1937, I think.

In 1943 they were selling off all the assets; we’ve actually got documents here showing the assets that were being sold because the war effort was coming, and they wanted the money for the war effort.

That school started at Ohinemutu; Te Ao Marama was the name of the school. It shifted in the 1930s to Whittaker Road. That building is still there to this day.

By 1962 the arts were gone again; there was only souvenir work being done. Hone Taiapa was approached to become the master carver of NZMACI. That was 1963; under that Act, the idea was to perpetuate Māori arts and crafts again, and virtually the Act that we’re under now is very much the same as the first Act; there’s not a lot of difference in it.

Of course, we’ve had a few amendments to it but it’s pretty much the same thing. So, the importance of that Act is to maintain, and a lot of people don’t even know that the Act existed. So, the idea was to perpetuate Māori arts, crafts and culture. If you look on the front of the old arts and crafts building, there’s a plaque with a proverb, “ He whare i whakaarahia i roto i te pa tuwatawata o nga tumanako”. Which says, “don’t build a wharenui outside of a palisaded pā because it’s going to be fodder for fire. Build it inside where it’s safe”.

It’s telling you to keep your arts and crafts safe within the structure of the building. There are other numerous interpretations of that, but it comes from a proverb.

Hone Taiapa & the first intake in 1969

When you say keep the arts and crafts safe within the structure, the idea of that is within New Zealand Maori Arts and Crafts Institute, under the Act.

If you look at the original story behind the whakataukī, the actual incident happened down in the Taranaki area (I think). The story went that the chief built his wharenui outside of the pā and unfortunately his enemies came along and burnt the structure with him and his family in it. He managed to get his son out before it happened knowing that the boy would go away, grow up, come back and avenge what had happened to him and his family. That’s what happened. But when the boy came back as a warrior chief and he took his utu (revenge) out on those people that burned his family, he built his house, inside the palisaded pā where it’s safe. There’s the origin of that. There are other interpretations of it floating around but that was the story that Hone Taiapa gave me. Nothing better than getting it from the horse’s mouth.

Can you talk to me a bit more about how you take that whakataukī and put it into the New Zealand Maori Arts and Crafts Institute concept.

Well, when that was put there in the 1970s, they started to put palisading right around the whole place, which was the proper thing to do because it’s making the building safe. Whether Hone was instrumental in getting them to do that because of that whakataukī is anybody’s guess.

That’s a really interesting, helpful history. If you reflect back to 1926, and the 1963 Act, and us here in 2024 now, how do you reflect on that time and where the objectives of this place are in perpetuating Māori arts, crafts and culture.

I remember in xxxx the Government sent a representative, wanting to know what the Act had done and achieved since it started. The information they got back staggered them. The number of people we’d taught. The number of meeting houses that had been done through this institute. Where they were, pan-tribal and so on. And our association with different iwi around the country. Not just the carving, weaving too.

When Emily Schuster was the head weaver, she would go out to different marae, teaching. I remember her saying, she taught over 5000 women how to weave. That’s all part and parcel of this Institute. There’s a huge legacy. We’ve helped a lot of people in a lot of ways with arts and crafts. It’s significant.

Do you have any idea how many students have come through in your time?

48 intakes, from 83 iwi, with 161 artists.

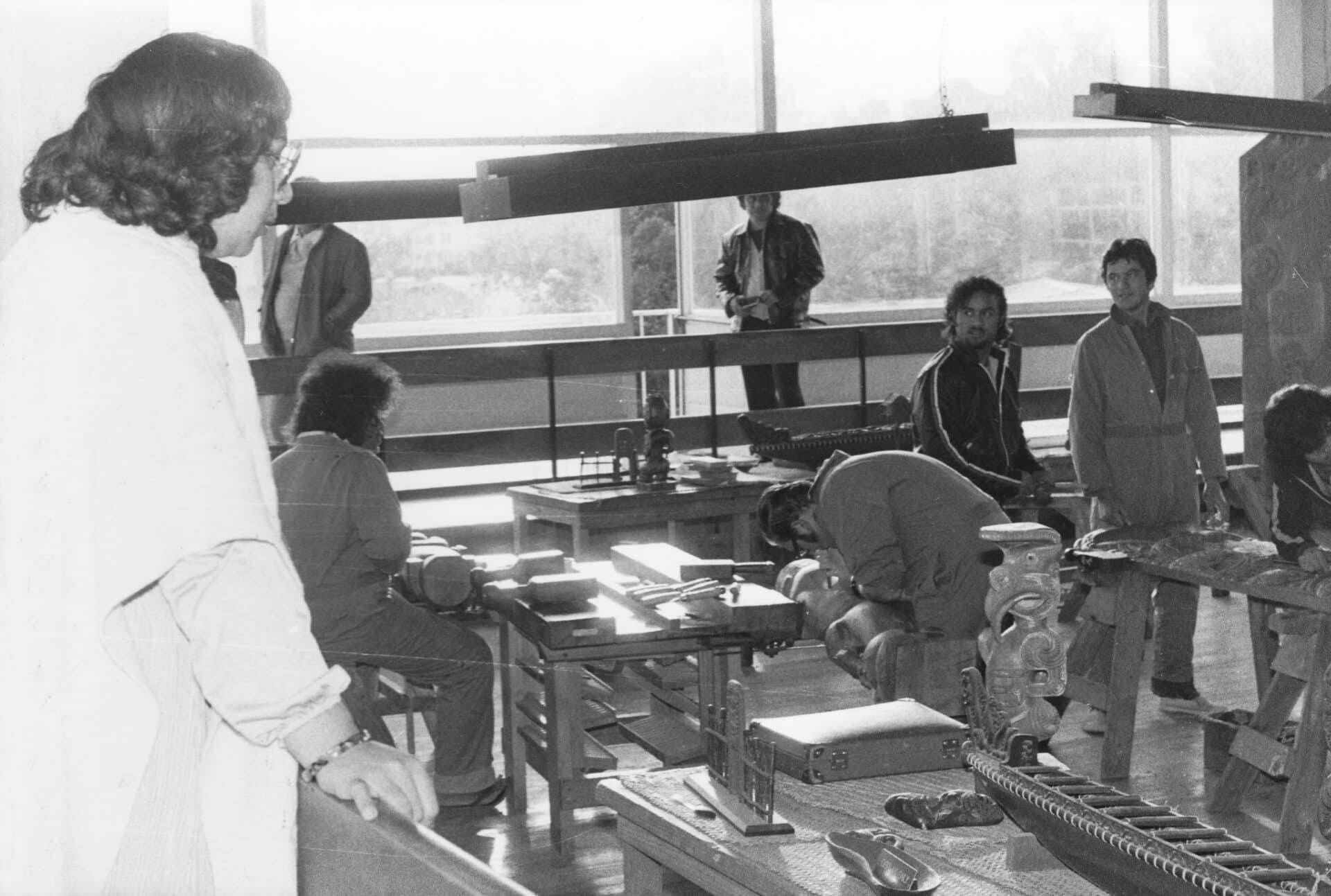

Clive with tauira

Clive with tauira

Clive with tauira

How many marae would NZMACI as a whole have worked on do you think?

Let me count, this is just off the top of my head, I’ll have to check my records:

- Hangarau at Tauranga

- Te Aronui a Rua here at NZMACI

- Hoani Waititi in West Auckland

- Tarawhai

- Moko at Te Puke

- Rongomainohorangi at Tauranga

- Pukenga

- Wharekawa at Kaiaua

- Matai Whetū at Kopu

- Tutereinga at Te Puna

- Mataatua

- Atiamuri

- Kearoa at Horohoro

- Rongomaipapa at Horohoro

- Te Whanau anō at Tokoroa

- Ōhinewaiapu at Tikitiki

- Tuhoromatakaka at Whakarewarewa

- Waiteti at Ngongotaha

- Mataura

- Airforce base marae at Ohakea

- Rongomaraeroa o ngā hau e whā at Waioru Army base

Successful graduates who have made careers in carving since leaving NZMACI and are now master carvers in their own right, include:

- Lyonel Grant

- Albert Te Pou

- Roy Toia

- Gordan Hadfield

- Fane Robinson

- Ricky Manuel

Clive & tauira working on Hoani Waititi marae 1979

At what point does someone become a master carver?

For me, you don’t put the name on yourself, others do. Unfortunately for me, I had to, I was appointed to the position, master carver (Tumu Whakarae) here in 1983. It was a Board appointment; I still have the letter of appointment. I have my 2IC’s appointment letter, which was Lyonel Grant, as well as Albert Te Pou’s.

As we look to the future, with everything you’ve learnt, seen and taught over the last 60 years, what do you think is going to be important, looking into the future now?

For me it’s the perpetuation of traditional Māori carving, arts, crafts and culture.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

It’s been a real honour and a pleasure to part of the journey. I’ve had an amazing career, but I’ve always tried to stick to the principles of the Act and to what I was taught and the ideologies that my master had taught me. I’ve tried to maintain that; that was my main goal. As he said when we started, you come here to learn this art to pass it on to the next generation. I’ve never forgot that; that’s what I’ve tried to do. Most of my life has been around that. Once I realised the importance of the information that I gathered over the years, I thought, that’s not for me now, it has to be shared. It doesn’t belong to me; it never will be.

How do you think you’ll continue to share all of that? What would you like to see happen with all your amazing records you’ve kept?

We’re setting up an archival system here now. When I first started the school, I started doing a manual. I noted that a lot of our students were going home, yes, they could carve alright, but when asked for information, they couldn’t answer them. I started doing lectures at that time as well. With help from Mauriora Kingi (who worked at the Ministry of Māori Affairs at the time), the manual ended up being quite thick; it had anything and everything in it. The trouble was that the young guys didn’t appreciate what they had. There was papers lying all around the floor. Now we want to rekindle that; this time we’re going to bind it into a book, properly referenced and everything.

ENDS